The Site

Welcome to Çatalhöyük, one of the most important archaeological sites in the world. Since the 1960s, excavations have uncovered a densely packed Neolithic (New Stone Age) settlement which dates back 9000 years.

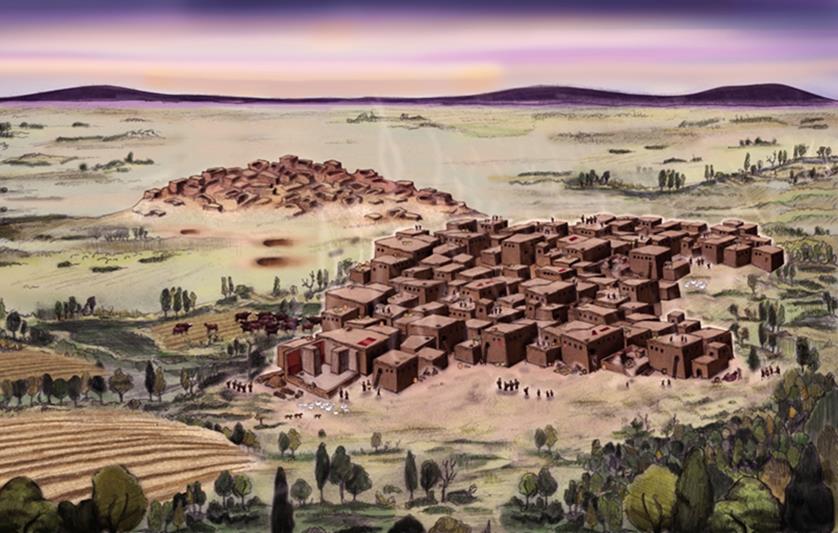

Today all that is visible on the surface of Çatalhöyük is two mounds: the smaller and more recent to the west of the site and the larger and more ancient to the east. However, scratch beneath the surface and the remnants of one of the most complicated societies of its time are revealed! A team of experts from around the world are currently working together to understand the lives of the people who lived here.

Discover what we currently know about Çatalhöyük and its people by exploring The Rise and Fall of a Neolithic Town, Architecture, Life at Çatalhöyük and The West Mound.

The Rise and Fall of a Neolithic Town

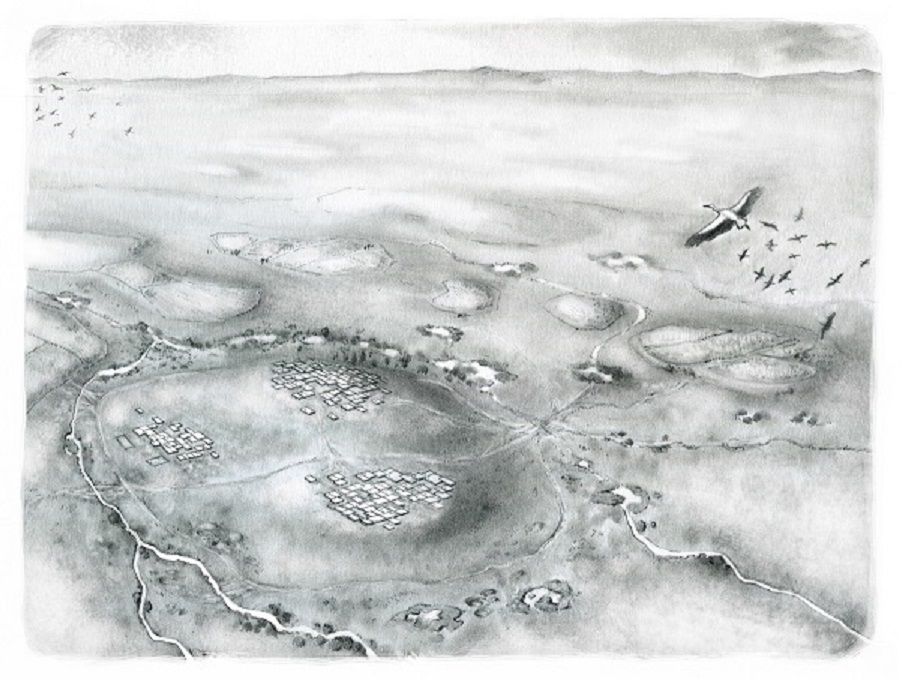

Let’s take a journey back 9,000 years to 7,400BCE when people first settled at Çatalhöyük. In this period, the site was situated in a wetland where the climate was moist and rainy. A wide range of resources were available including fish, water birds and their eggs. On the drier ground there were agricultural fields, and herds of wild animals could be found roaming the plain.

This was a society undergoing continual transformation. By 6,500BCE we can see radical changes in behaviour. More efficient cooking pots were developed, which in turn created time for other activities. Domestic cattle and milk were introduced and there was an increase in housing and population density. Burials and ritual behaviour also became more elaborate. It is at this time that we begin to see the emergence of many of the decorative features that Çatalhöyük is famous for, such as figurative art. At its peak 3500-8000 people lived, worked and died here.

In the later period of occupation at Çatalhöyük, inhabitants of the East Mound started dispersing to the many other sites that grew up on the Konya Plain. One of these was the West Mound. Interestingly over the millennia, surrounding communities continued to use the East Mound for burial and other activities. Clearly this remained a special place in the landscape.

Architecture

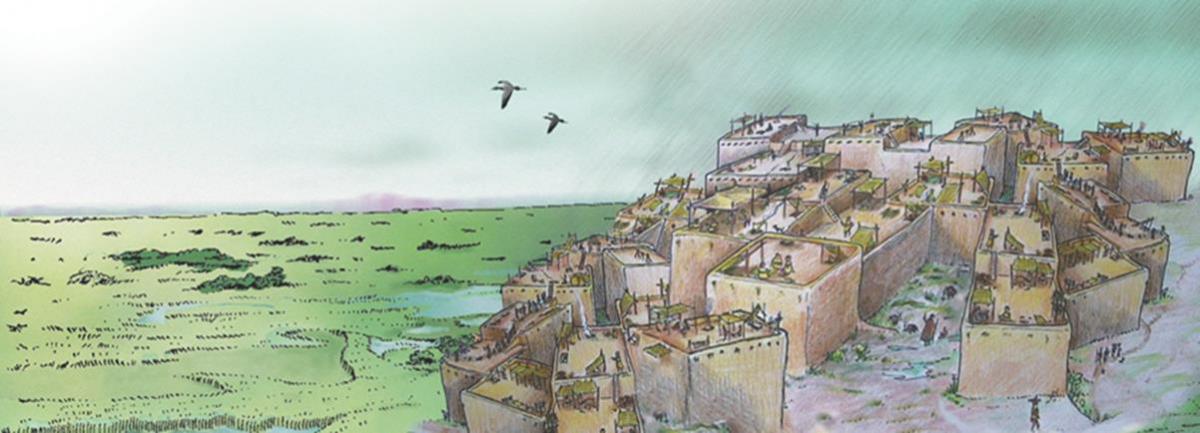

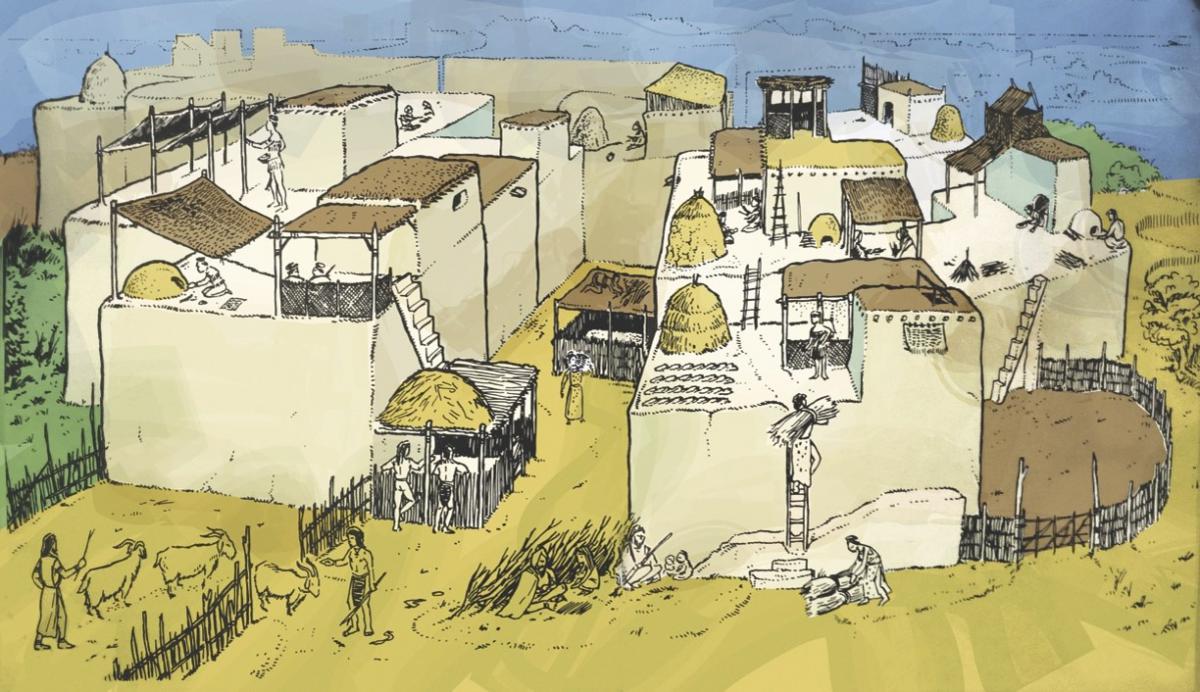

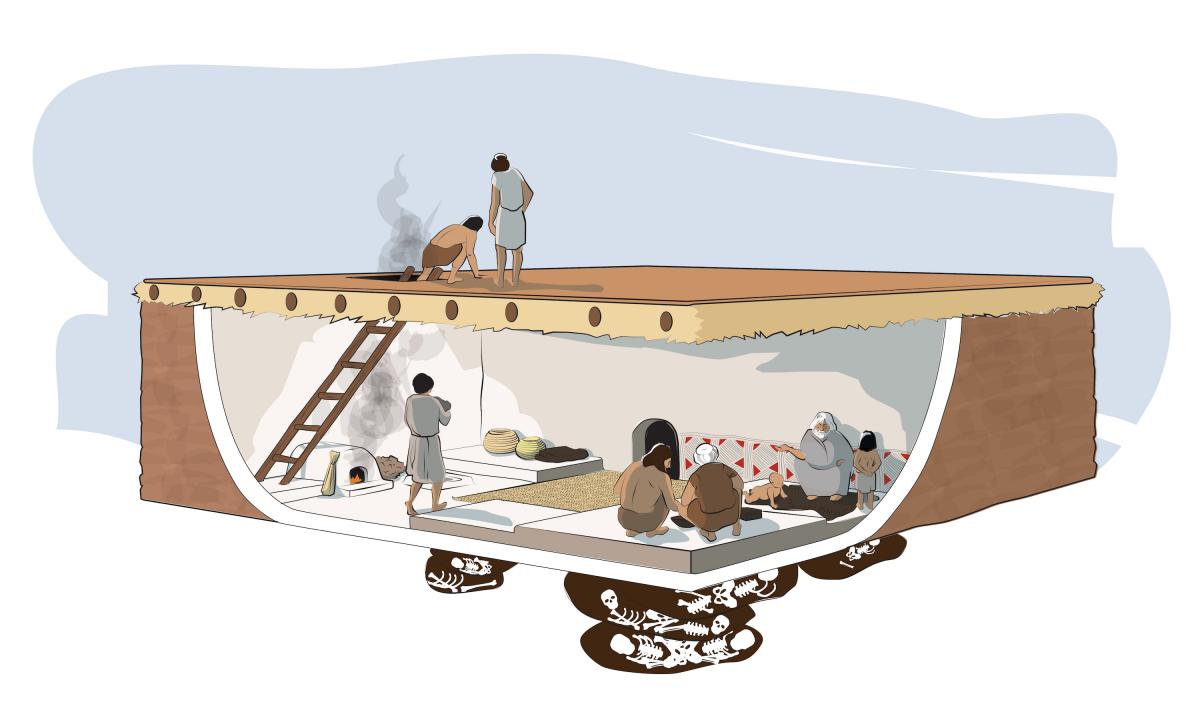

One of Ҫatalhöyük’s most defining attributes was its inhabitants’ gradual, continuous building and rebuilding of their houses. These houses were very important to all aspects of their lives: material, social and ritual. Houses were roughly rectangular and closely built together with no streets in-between. Instead, people moved around on roofs and accessed their homes down a wooden ladder via an opening in the ceiling.

All the houses found at Ҫatalhöyük are different in shape and size, yet most follow a general layout. Each central room had an oven below the stairs where people carried out domestic tasks such as cooking. Raised platforms within the rooms were used for sleeping and other domestic activities. Beneath these platforms inhabitants buried their dead. Side rooms were accessed off the central room providing essential storage areas.

Like we do today, people decorated their homes. At Ҫatalhöyük we see white plastered walls and floors, on which elaborate paintings were made depicting hunting scenes and geometric patterns. The walls were constructed of mud bricks. Evidence suggests that the wet clay mixture was either placed directly on the wall between wooden boards or constructed using mortar and sun-dried bricks. This tradition seems to have carried on over time to the present day, as we see similar construction methods used in the local region now. Thick wooden posts were erected in the central room and may have been used to strengthen the structure, as well as create internal divisions of space.

People took great care of their houses and meticulous planning was an important part of the building process. We know that houses were continually infilled, often burnt and rebuilt throughout the site’s occupation, eventually creating the mound that we can see on site today.

Life at Çatalhöyük

Daily life took place both at the settlement of Çatalhöyük and away from it, in the surrounding landscape. Men and women led very similar lives, with analysis of human skeletons showing generally identical diets. Infant mortality was high, as were the risks for women during childbirth. However in general, people lived healthily and actively. They ate a varied diet containing both animal products such as fish and beef and plants such as barley and wheat. Remarkably, upon their death, people were buried under the floors of houses. The bodies were often tightly bound in a flexed position and placed in a simple grave with few or no artifacts.

People crafted obsidian and bone tools as well as ceramic materials. The obsidian and bone were not only used for subsistence but also to create interesting objects such as clay figurines and beads. Many of the tools themselves were also beautifully decorated. Obsidian was sourced from Cappadocia and Eastern Turkey, and some traders even travelled as far as the Red Sea to obtain baskets and shells. These were a people who valued artistry and aesthetics.

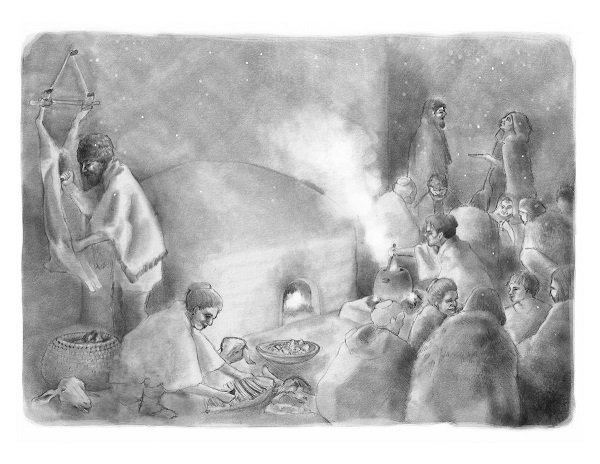

Surprisingly for such a sizeable settlement, food, tools and other resources were shared equally and used by all. Ritual activities at Çatalhöyük revolved around hunting, death and animals. Wild bulls were needed for feasts, and there were probably taboos or special meanings for leopards and bears. Today, many people believe that a mother goddess was worshipped at Çatalhöyük based on the discovery of numerous female figurines. However recent reinterpretations of the data have suggested that male and animal figurines were just as common as their female counterparts, if not more so. Equality in all senses appears to have been of primary importance for the people of Çatalhöyük.

The West Mound

Occupation of the West Mound of Ҫatalhöyük started later than its eastern counterpart and continued long after the desertion of the East Mound. The area between the mounds is today taken up by fields, but archaeologists believe it may once have been the location of the Çarşamba River. The mound is commonly associated with the Early Chalcolithic, the period where we first begin to see painted pottery. Available dates suggest that the mound was occupied between 5,900-5,600 BCE. Ҫatalhöyük is special in that it spans this Late Neolithic to Early Chalcolithic transition.

Reasons for the establishment of the settlement on the West Mound are not clear. One hypothesis suggests that the Çarşamba River changed its course causing people to move in order to live either closer to or further away from the water. It appears to have been a gradual transformation with cultural differences slowly emerging between the East and the West Mounds. These differences are most obvious in the buildings as we find no evidence for burials under houses, wall paintings or the infilling of abandoned houses.

Pottery also changed with the emergence of beautifully decorated pots. This may have been due to a new concern for entertaining guests with impressive painted serving vessels. Although we see evidence for such change in serving practice, diet remained much the same. Only cattle seem to have been consumed less and were no longer used for bucrania or other bone installations. These mark yet more cultural differences between the two mounds.

The reasons why these differences emerged, and why people chose to occupy the West Mound in the first place, remain open to interpretation. Investigations into this fascinating site are set to continue in the future.