By Andrew Henderson

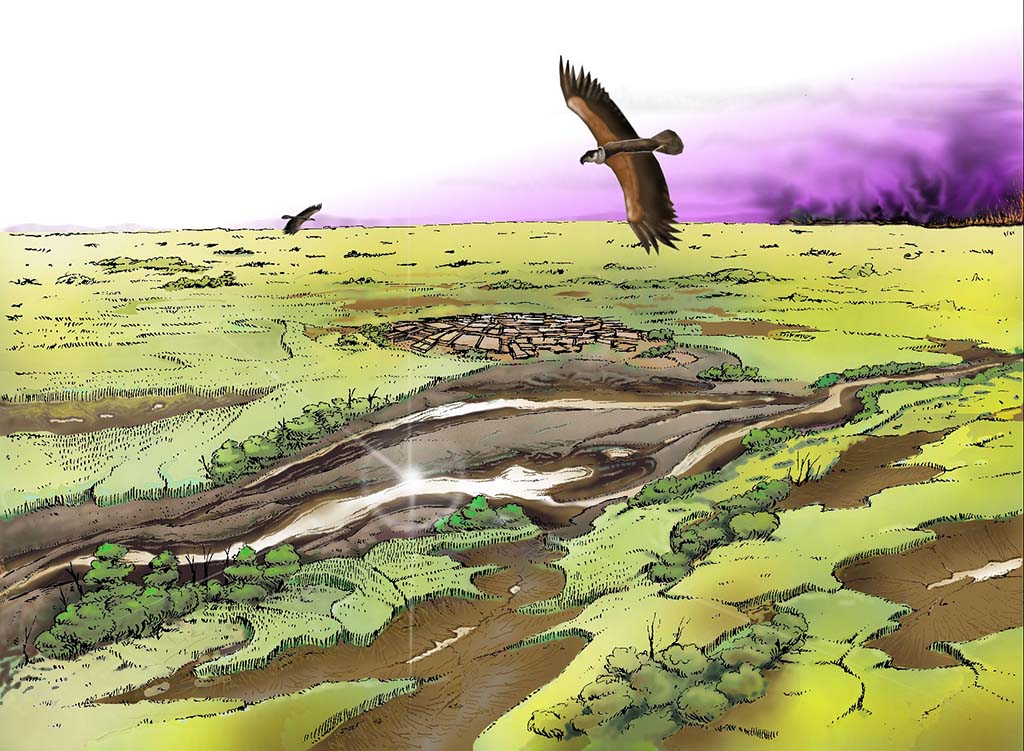

Images are some of the most powerful interpretative tools in archaeology. As has already been discussed on this blog, the image making process is laden with complexities and should be considered as rigorous as any textual description. Yet equally, as I see it, the true value of images lies in condensing multiple ideas and theories into one visual space, allowing us to imagine the past in a way which books or articles may struggle to achieve. Therefore, if we are to acknowledge the power of images and place them as equals to academic articles, then we need to begin to think about them in the same critical fashion as we would any academic publication. As part of my latest research at Ҫatalhӧyük, reconstructive images are being subjected to the level of analysis and scrutiny which they deserve.

As part of a project I conducted for my postgraduate degree in Digital Heritage at the University of York, 8 images of various mediums which have been produced at Ҫatalhӧyük since 1993 were selected for study. These images were put through a series of analyses in order to identify elements such as their features, why and how they were produced and how audiences react to them. This process involved applying theories from both archaeology and other disciplines, such as geography and marketing. Not only does this type of research allow for an appreciation of the incredible time and effort that the artists at Ҫatalhӧyük put into their work, it can also influence the way in which people understand the site.

An example of the value of researching images can be seen in the differences between how audiences view computer generated images and illustrations. By interviewing visitors to Ҫatalhöyük, I found that many generally had greater confidence in photorealistic images and were therefore less likely to question what they were seeing. Illustrations on the other hand were often viewed as being far more interpretative, encouraging more discussion and debate.

This type of information opens many possibilities. For instance, in certain contexts it is desirable to encourage people to question what they see and imagine the past in their own way. As such, elements which suggest uncertainty may be added either visually or in a caption to a computer generated image to facilitate this. Conversely the level of archaeological accuracy behind an image may, at times, be emphasised or altered in order to provide a more accessible means for various audiences to engage with complex theories. Trying to mix archaeological data, imagination and artistic licence is one of the many challenges faced by archaeological image producers.

Ultimately then, through gaining a greater understanding of the images at Ҫatalhöyük - from production to reception - my research hopes to help inform their future production and use. Through this it is hoped that we will be able to continue to view imagery which not only displays the results of archaeological research, but also encourages us to think imaginatively, creatively and critically about life in the Neolithic.