ÇATALHÖYÜK 2004 ARCHIVE REPORT

| |

CULTURAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL MATERIALS REPORTS

Figurines and Miniature Clay Objects

Carolyn Nakamura and Lynn Meskell

Team: Lynn Meskell, Carolyn Nakamura (Columbia University) and Ali Umut Türkcan (Eskisehir University)

Abstract

The 2004 season was a particularly productive year for figurine research both in terms of finds and data management and analysis. Seventy-two objects and fragments were excavated and recorded. Notable finds include a marble female figurine (10475.X2) resembling Mellaart's category of ‘mother goddess' from disturbed burial fill in the South Area, and a marble anthropomorphic figurine from a floor cluster (10264.X1), and animal figurine cluster (7958.X1-X6) from bin or platform fill from the 4040 Area. Two new members, Lynn Meskell and Carrie Nakamura, joined Ali Türkcan and implemented a new program for the systematic study of the figurines. The most substantial work accomplished this season involved the design and execution of a new figurine and miniature object database containing over 1250 pieces. An initial review of the inherited records, material corpus and related data sets strongly indicated the need for a new and expanded database inclusive of all figurine objects and fragments from the field and Mellaart collections, and miscellaneous miniature shaped clay objects. The database design process did not simply involve archiving the collections, but engaged a critical rethinking of analytical and interpretive categories oriented towards a more integrative approach to figurine studies. Such an approach seems necessary given the multiple areas of cross-over between the figurine corpus and other data sets in terms of clay fabric sourcing, production and firing and representational imagery; within these practical and conceptual fields, certain distinct boundaries between data categories such as figurines, pendants, clay balls, wall art, and bucrania break down. Refocusing figurine research towards such areas of overlap prompts a productive rethinking of our taxonomic framework in terms of processes of resource acquisition, technological and gendered production, and use rather than in terms of the end product. A long-term goal of this new program aims to reposition figurine research as providing important social information about these processes in everyday and special activities at Çatalhöyük.

Özet

2004 yılı fig üri n araştırma projesi, çıkarılan buluntular ve veri analizi açısından oldukça verimli bir yıl olmuştur.Yetmişiki tüm obje ve obje parçası bulunmuş ve kayda geçirilmiştir. Önemli buluntular; Güney alanında bulunan bir gömüden çıkan, Mellaart'ın ‘ana tanrıça' olarak tanımladığı mermer kadın figürini (10475.X2), taban dolgusundan çıkarılan mermer bir antropomorfik bir figürin (10264.X1), platform veya ambar dolgusundan çıkan hayvan figürinleri topluluğu (7958.X1 -X6). Bu sene, Ali Türkcan'a Lynn Meskell ve Carrie Nakamura katılmış ve sistemli bir figürin çalışması için yeni bir program geliştirmişlerdir. Bu sezonda yapılan en önemli iş, 1250 parça minyatür obje ve figürinin kaydedildiği veritabanının hazırlanması ve işletilmesidir. Daha önce tutulmuş kayıtlar, buluntular ve bunlara bağlı veri grubuna bakıldığında, bütün figürinleri ve figürin parçalarını, Mellaart koleksiyonunu ve çeşitli kilden yapılmış minyatür objeleri de kapsayan geniş bir veritabanına olan ihtiyaç ortaya çıkmıştır. Ortaya çıkan veritabanı, yanlızca koleksiyonun arşivini oluşturmak amacına yönelik olmamış, figürinler üzerine yapılan araştırmada daha tümü anlamaya yönelik bir yaklaşımla, analitik ve yorumsal kategorilerin, eleştirel düşünme süreci ile bütünleşmiştir. Böyle bir yaklaşımla; figürinler ile kil yatakları, üretimi, pişirilmesi ve temsili görüntüsü gibi diğer veri grupları arasındaki çoklu bağlantı göz önüne alındığında, bu pratik ve kavramsal alanlar içinde, figürin, kil top, pandantif, duvar resmi ve bukrania gibi veri katerogorileri arasındaki keskin sınırlar ortadan kalkacaktır. Figürinle ilgili araştırmalara, birbiri ile bağlantılı bu alanlar açısından tekrar bakılması; kaynak elde etme süreçleri, teknoloji, cinse bağlı üretim, ve son haliyle bulunan üründen daha çok, kullanılan ürün açısından ele almak, taksonomik çerçevemizi üretici biçimde tekrar değerlendirmemize yol açacaktır. Bu yeni program, uzun vadede, figürinle ilgili araştırmalara,Çatalhöyük'teki günlük yaşam ve günlük yaşamın dışındaki özel aktivitelerin süreçleri ile ilgili sosyal bilgiyi elde ederekten tekrar yön vermeyi amaçlamaktadır.

Introduction

This season was notable for two rather sensational figurine finds, one of which made the press headline, “…Mother Goddess found at Çatalhöyük;” but the most important and productive figurine research this season involved the less glorified work of implementing a new research program, the core of which involved constructing a new database. Although often unacknowledged, the pragmatics of database design engage and shape the particular ways in which we interrogate and interpret data sets. Databases do not store objective information, but organize, document and demonstrate various impressions filtered through particular classificatory schemes operative in our examination and description of archaeological materials. A notable objective of the Çatalhöyük project aims to foster research that not only moves across taxa, but also across traditional specializations within the project.

While certain categorizations are useful in the archaeological organization of objects, it is perhaps more productive to also be able to complicate our heuristic strategies and try and restore some emic or contextual meaning to the frame. Some categories are clearly meaningful for us: figurines, wall paintings, ceramics, lithics, worked bone, and so on. In archaeological excavations such as Çatalhöyük these categories are being collapsed and reorganised to attempt a closer fit with ancient systems of meaning. What if the sorts of things one makes from clay all belong to one coherent category? Suppose magical items whether clay, wax or wood, were more meaningfully grouped from the outset. These strategies can be pursued later in more synthetic works but often are not followed up on, leaving a static and unrepresentative picture of material life in place. Archaeologists tend towards morphological, followed by evolutionary, classification whereas it is conceptual taxonomies that allow insight into past meaning.

Although figurines offer a particularly rich corpus for more synthetic and dialogic approaches, previous work on this corpus has remained conspicuously unengaged from such research. Redressing this neglect, we implemented a new program to bring figurine studies into alignment with the project's more democratic goals. This process required a critical rethinking of the category of figurines itself such that it could accommodate the kind of integrative and cross-data inquiry so important to understanding the social past of the site. The construction of a new database did not simply consist of archival work, but involved ongoing dialogues with numerous specialists (IT, ceramic, stone, excavation, architecture, clay ball), and the consideration of the specifics of individual objects and general patterns that emerge from the corpus as a whole. This practical reworking of a descriptive and analytical taxonomy also guided us towards certain thematic and theoretical implications. In particular, we found themes of visuality, masculinity, modes of representing and viewing, crafting, personhood, hybridity, intentionality and mastery to be most compelling and productive in terms of yielding important social information. Future research will explore and theorize these issues more fully, and engage in collaborative experimental work on clay fabric, sourcing, firing, crafting, deposition, and fingerprint analyses.

Work Done

We accomplished a significant amount of work this season, the majority of which concerned sorting, documenting, and organizing the figurine corpus such that the data could be readily accessible and available for anyone to study. Due to the way in which the figurines had been studied previously, there was no systematic record of the total number of objects in the field collection, much less the entire Çatalhöyük figurine corpus because many of the fragmentary and ‘mundane' pieces had been excluded or consolidated under general types. Endeavoring towards a more encompassing approach, we focused on employing a scheme that considered all materials seriously, including the fragmentary pieces, abbreviated and non-human forms, and Mellaart figurines. This goal required a reassessment of the inventory of the field collection, the published museum collections in Konya and Ankara, and Naomi Hamilton's publications, databases and research notes.

It is also noteworthy that this season we were granted permission to examine and photograph the figurines in storage and on display in the Konya Archaeological Museum, something that team has not been allowed to do for five years. Unfortunately, the permission came at the end of the season and we were able to spend only one afternoon examining the collection. We viewed several pieces for which we have no record and plan to return to the museum next season to complete documentation of this entire collection.

Since there are over 1250 pieces comprising the Çatalhöyük figurine corpus, about 800 of which are in the field collection, it was impossible for our team of three to fully document all of the objects in a single short season. Given this restriction, we prioritised the construction of a ‘skeleton' database comprising the entire figurine corpus, but with data entry restricted to essential identifying information (see ‘Database' below) and photographs in most cases. However, we did require a substantial sample of fully recorded objects in order to test the workability of the database as a practical tool itself; these detailed examinations focused on the previously unrecorded Mellaart objects from the Ankara museum storage (MELLET, 86 objects), and the field collection beginning from the most recent excavation years. We digitally photographed multiple views of all objects (over 1500) in the 1993-2004 field inventory including the MELLET pieces, and about 25 objects from the Konya Museum.

Database:

The database aspect of the project, although perhaps evocative of tedious, repetitive and somewhat inert mental and motor activities, also anchored very productive critical discussions concerning traditional figurine category constructions and studies. Two main concerns informed the database design process: 1) the rethinking of the taxonomic architecture towards more open and balanced figurine research and 2) the goal of integration between the figurine corpus and other data sets that share common material fabrics, representational forms and technologies, thus promoting collaborative and cross-field research.

Figurines commonly evoke notions of the Mother Goddess, the female domestic sphere, and ritual or cultic activities, but such ideas alone do not account for the striking diversity of the Çatalhöyük assemblage which hosts objects spanning a spectrum of highly elaborated to abbreviated forms, human and animal representations, and range from careful to quick disposal/depositional contexts. Although, some of the objects likely derive from ritual activities, the majority is associated with contexts suggestive of more everyday practices. Furthermore, a strict division between the 'everyday' and the 'magical' or 'ritual' might not have been operative in the past; allowing for this possibility marks another example of our concerted attempt to challenge taxonomic structures or binaries in all levels of interpretation. Given these considerations, we have conceived of a systematic classification structure that resists privileging the female/anthropocentric/ritual-oriented gaze that has previously constrained figurine research; rather we desire a scheme that unpacks descriptive categories as much as possible and gives equally footing to a diversity of interpretive possibilities.

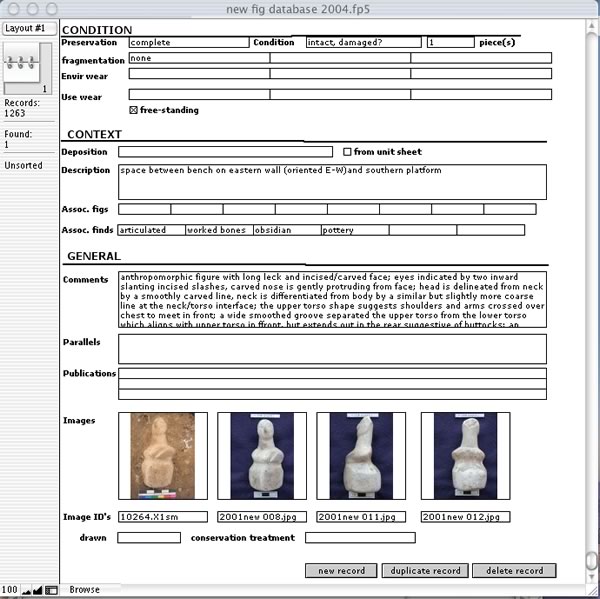

Given the second consideration of collaborative research and integration, our classification scheme also considered those of other specializations on the site. Working with database specialist, Mia Ridge, we consulted Nurcan Yalman's pottery database and Sonya Atalay's clay ball database to coordinate our descriptive categories concerning clay fabric with their systems. Instances of categories for which there were no established comparisons, such as form, elaboration and treatment, we used conventional terms and/or nested categories. Where possible, we defined extensive value lists to constrain the range of descriptive terms used for data entry. Many fields were also designated as 'one to many' allowing for different and multiple interpretations (see Table 1, Appendix 1). This resulting system produced a rather extensive database that is still a work in progress (Figure 1a,b). As more databases become integrated with the main excavation and finds databases, we anticipate adjusting our system to better accommodate multi-strand queries across data sets.

At the outset of our first season, we also found ourselves engaged in a test-run of sorts; the project's ambitious goal for a web-accessible integrated database by the end of 2004 compelled us to conceive and design a new figurine database that Mia could centralize with the main Access system. Our part included creating a sophisticated and integrative standalone figurine database in Filemaker Pro 7. But given the time constraint (two weeks), the database could not be successfully interfaced with the main Access excavation database as a fully functional research tool. By the end of this initial period, however, Mia had developed an Access interface for the figurine database that allowed one to view, but not enter data. This result was largely due to time constraints and lack of familiarity with the Çatalhöyük materials. When we have fully examined the figurine corpus, we will be in a better position to consider potential areas for cross-categorization across other data sets and think through a design that can adequately address these issues. We must therefore emphasize the present state of the figurine database as a promising work-in-progress and we will continue to collaborate with Mia and other specialists towards implementing a well-integrated figure database.

Object Documentation:

The resilient intellectual legacies of figures such as James Mellaart and Marija Gimbutas have, perhaps, irrevocably secured the association of Çatalhöyük with the Mother Goddess; but one might find it astonishing that representations of definitively female figures make up less than 2% of the entire Çatalhöyük figurine corpus (Percentage is not definitive, but based on preliminary tallies and estimates ). Although the nascent state of the database prevents us from presenting any precise counts here, the bulk of the finds seem very fragmentary and predominantly consist of clay examples of zoomorphic forms (Fig. 82a), abbreviated anthropomorphic forms (Fig. 82b), and horns (Fig. 83). These basic clay forms also comprise most of the previously undocumented MELLET (1960s Etutluk (study) collection) materials and figurines from the Mellaart spoil heap dug by students involved in the TEMPER project. Such results suggest that ‘mundane' types were likely present during the 1960s excavations, but rather overlooked in favour of the more elaborated human figures. Provocatively, we also identified heads and bodies that appear to have attachment holes, not previously noticed or noted.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 82a: Examples of quadrupeds

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 82b: Examples of abbreviated forms

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 83: Examples of horns

2004 Finds

This season, excavations recovered seventy-two figurines and miniature clay objects from the South, South Summit, and 4040 Areas. Tables 47-48 present a basic summary of the 2004 finds.

Table 48: 2004 Figurines and Clay Objects by Form: Basic Counts

Table 49: 2004 Figurines and Clay Objects by Form: Detailed Counts

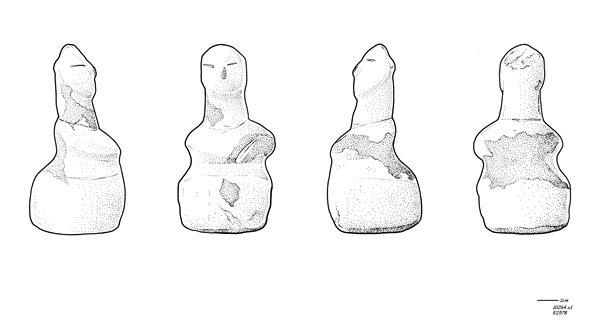

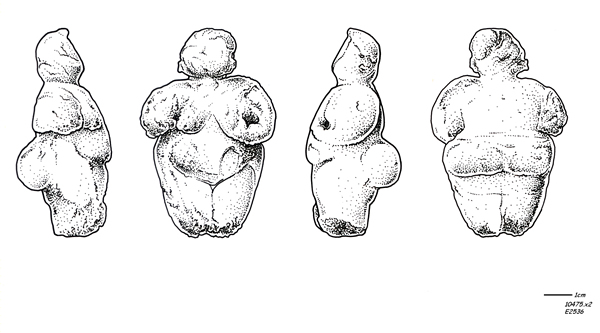

The two stone figurines unearthed this season were considerably larger and more detailed that the more ubiquitous clay varieties. 10475.X2 is reminiscent of Mellaart's ‘Mother Goddess' type from a mixed deposit of burial fill and 10264.X1 is an anthropomorphic form that is unsexed or has indeterminate or ambiguous sex traits from a floor cluster.

|

10264.X1 is a marble anthropomorphic figure with long neck and incised/carved face. Eyes are indicated by two inward slanting, incised slashes; the carved nose gently protrudes from face. The head is delineated from neck by a smoothly carved line, and the neck is differentiated from the body by a similar but slightly coarser line at the neck/torso interface. The upper torso shape is suggestive of shoulders and arms crossed over the chest to meet in front. A wide, smoothed groove separates the upper and the lower torsos and is aligned with the upper torso in front, but extends outward in the rear emphasizing the buttocks. |

|

Figure84: 10264.X1 9.1cm (h), 4.6cm (w), 4.5cm (th) |

||

The figurine appears to be unsexed, however, there is some ambiguity since the overall shape of the head and neck appears phallic, and an off-centered (towards the left) pubic triangle appears to be coarsely incised on the bottom front at a later date (this may also be accidental). Also, some gouging just to the right of the triangle and a large diagonal gouge across the left arm/chest are more recent. There is dark brown discoloring on the nose and left arm/chest, and a wide band of reddish-brown coloring in the wide groove/waist on the back. The figure is very similar to Final Neolithic Cycladic and Cypriot Neolithic figurines.

Context: This figure derives from Space 227, in a room located west of building 47 in the 4040 Area. Pottery suggests this space dates to level V-IV. 10264.X1 was part of a cluster of objects additionally comprised of obsidian, worked stone and bone, and animal bone. The cluster was found on a plastered floor beneath refuse fill and wall collapse.

10475.X2 is a robust female figure made from marble or calcite (highly corroded) with divided legs, large buttocks, and a slightly protruding stomach. The figure holds its arms up to its breasts and incised lines indicate the breast divide, pubic triangle/stomach, and divided legs on the front; similarly incised marks delineate arms, divided legs, and a horizontal detail across the upper legs on the back. The head and face appear to have been worked, but possibly modified or defaced , suggesting that no facial details were executed or were removed. There is a suggestion of hair or a head-cap. Voids are present on the bottom of the legs and between the chest and arms (larger on the left side) and there is a deep groove on the top of the head. Yellow-orange staining appears on the upper back, buttocks, down the back/side of left leg, around neck, face and top of head; conservators believe this staining to natural and organic. |

|

|

Figure 85 10475.X2 7.5cm (h), 4.9cm (w), 3.5cm (th) |

||

Context: This figurine was excavated from Space 202 in Building 42 in the South Area. This unit represents a very mixed deposit of re-deposited fill of a disturbed grave. Intrusive midden-like deposits also complicate this context.

Implications and Future Research: Themes and Goals

The Çatalhöyük figurines and miniature shaped objects present a wonderfully rich and diverse corpus of materials. It is not surprising then, that such evocative materials should incline us towards a number of promising thematic directions. Below, we briefly touch upon some of the main themes and directions that will inflect our future research on these materials.

Video and Visuality

We are currently considering the role of the video since it provides a unique way of capturing the handling of figurines. Since figurines were made by hand and ultimately circulated from hand to hand, it seems an obvious avenue to pursue. Through use of video, we attempted to capture the embodied nature of handling the objects as well as the various viewpoints afforded us when moving the image in various 360° rotations. Through this technique we highlight the tactile nature of the object, taking it further than conventional photos or drawings of various angles, stressing that it is necessary to experience holding and circulating the object. Here we are particularly interested in the multiplicity of views and the various visual cues or puns one might observe from this unconventional technique. This is especially true of the larger figurines such as 10264.X1 that clearly have ambiguous or dual sexual characteristics.

In seasons to follow we hope to take advantage of a wide range of media, photos, video, drawing and virtual reconstructions, which would potentially connect us with the work of John Swogger.

Materials: Technology and Sourcing

It will be important to examine various practices concerning the procurement and technological production of figurine fabrics. Most commonly, we find that figurines are predominantly made from clay and, less often, stone. We are exploring the possibility of delineating connections between material, practice, form and meaning. This season, the two ‘finest' figurines (10264.X1, 10475.X2) were anthropomorphic forms carved from marble, a non-local material found more than 100 kilometers away, while zoomorphic and abbreviated forms were exclusively made from clay. The fabrics used to manufacture the clay figures tended to be fairly homogenous, consisting of a relatively pure, fine silty clay. Such fabric is similar to that used to fabricate miniature geometric objects No doubt, clay occupied a central role in many of the daily activities at Çatalhöyük and we will be collaborating with other lab specialists who work with clay materials, namely Mirjana Stevanovic, Burcu Tung and Nurcan Yalman, to look at local clay sources, and fabrication and firing technologies. This joint effort participates in a concerted move towards pushing the limits of our archaeological classification systems that tend to separate out object types rather than focusing on particular worldviews that may have seen across them; in the case of clay, we will explore the possibility of fabrication and materiality, themselves, being more salient unifiers than form and function.

Traces of Sex and Age: Fingerprint Studies

Despite the enduring association of Çatalhöyük with narratives advocating a powerful role for women in early agricultural societies, recent research into sex roles and divisions at the site reveal a more complex and nuanced picture. Evidence largely points to a social reality in which sex was not often a salient or dominant determining factor of position or rank. This picture underscores the possibility that other aspects of social life likely provided areas for constructing social difference. For instance, much less research has focused on the activities of children in the past; but at Çatalhöyük, children are well represented in burials within houses. Figurines may also provide another material sphere that involved children. Sharon Moses (see below) is currently looking at the adolescent and infant burial evidence at the site and is also interested in exploring evidence for figurines as toys. One potentially rich area of figurine research yet to be explored concerns the question of who is making the objects. Many of the figurines are extremely small; the tiny abbreviated forms are particularly evocative of a child-like style. Here, ancient fingerprints might be able to shed light on the sex and/or general age group of some of the figurine makers. Fingerprint ridge pattern analyses of clay materials provide a non-destructive and effective technique of differentiating between male, female and children's hands from partial fingerprints (Cummins 1941; Cummins, Waits et al. 1941; Ohler and Cummins 1942; Rife 1990; Kamp, Timmerman et al. 1999; Stinson 2002) . During our review of the clay materials, we noticed that numerous figurines bore fingerprint impressions and we will undertake fingerprint analyses over the 2005 season.

Materiality and Making

There are several themes of contemporary interest that are key to this new figurine research, including materiality and world-making. Figurine work deliberates and engages a variety of considerations and activities, from local and technological knowledge to normative social forms and individual desires; specifics of maker, material, intention, skill and knowledge all inform the production, use and, in some cases, the destruction of the figurine. Here, we are expressly interested in the embodied processes of crafting that encompass a number of material perspectives, from the securing of materials from various resources to numerous forms of decision making, individual and material agency, techniques of making (including stabbing or maiming), placement, circulation, handling and the final depositional contexts of these objects and their concomitant associations. From an archaeological viewpoint we might explore the various relations between material, maker, rapidity and care in making and depositional context. Experimental work could inform us how quickly certain figures were crafted. The abbreviated human forms already indicate a certain rapidity in making and their ubiquity suggests that such practices could have occurred regularly, perhaps even on a daily basis. Were these more casual pieces the products of everyday activities performed by everyone or specific activities performed by a particular group? Furthermore, the materiality of each object must be taken into account, leading us to ask is fabric an outlay of investment an indicator of special status or purpose? Are expedient abbreviated forms any different from carefully carved stone examples? Does the skill base potentially tell us about their crafters? Where Mellaart's findings originally suggested that impressive finds occurred more frequently in his ‘shrine' areas, work on his spoil heaps by the Temper project indicates that his team missed many of the more abbreviated examples; the current project is also working to balance the picture of more complex examples carved from stone. This diversity of forms, materials and find contexts suggests that figurine work drew upon a diverse range of activities and intentions. A focus on the material processes and practices, rather than on products, can better address the dynamic aspects of social life and human experience that intersected with figurine worlds.

Figurines are also unique in their three-dimensional, tactile and portable nature. Unlike other forms of figurative representation, figurines invite the process of holding and turning in hand, allowing one to experience them from various viewpoints, as outlined above. This tactile and visual experience may have been an important consideration for the conception, fabrication and use of figurines. Issues of access also inform processes of making and circulation: who could touch, hold, and view certain objects and materials? We should also consider the performative aspects of certain pieces as well. In this vein, how may they have been deployed in certain settings, and were they considered agentic themselves, as apotropaic objects, intermediaries, mimetic copies, or images of self and others? The provocative findings of several shaped heads and bodies with attachment holes suggest that some examples had detachable parts or that in specific moments; certain objects could assume different identities or valences. This aspect of mutability might relate to specific notions or explorations of personhood.

We also might closely examine the prevalence of headless figures both in the figurine assemblage and in wall art. Although the neck does generally locate a likely breakage point, our initial impressions find that body fragments significantly out number head fragments in the figurine corpus. The idea of a headless body representing a deceased state of being is interesting but needs to be explored further, potentially through intersecting notions of materiality, personhood and dismemberment of both real individuals as well as figurines and other representations.

Critical attention to embodied processes of making and the dialectical relationship between persons and the material world anchors this broad suite of questions, which stand to address important issues of how people in the past experienced, lived and modified the material reality of their world.

Control and Mastery: The Miniature and the Copy

Figurines present a material idiom of craft, work, performance and creation that engages in a process of mutual constitution in which humans transform the world around them, and are in turn, transformed right back. Such is the reality of matter; it strikes back. This choreography of size, material, and form locates a ‘copy' that delivers the ‘original' under human control. Although such ideas tacitly underwrite notions of hunting magic that commonly ‘explain' the numerous ‘wounded' animal figurines at Çatalhöyük, ideas need to be fleshed out more fully in terms of human creation, experience, and intention. As ideas, beings, fears and desires come to inhabit a material reality of human design, the production and reception of the figurine itself becomes a dramatic form of experience, namely, the experience of mastery. Figurine work constitutes a material relation in which humans become all-powerful giants and masters of the diminutive petrified tableau of the figurine.

Miniaturization is especially pervasive at Çatalhöyük , but has yet to be fully explored within specific practices at the site. Many of the figurines measure less than a few centimeters in height, and several, even less than one centimeter. Another theme of our research will explore figurines as a mimetic gesture performed at scale of the miniature. The figurine miniature provides a locus for enacting a variety of desires, such as possession, mutilation, and domination, to name only a few. The scale of the figurine, therefore, invites activities of play and fantasy. Play, as a pure form of activity for its own sake, constitutes an arena of limited and provisional perfection, in which one is the master of destiny. We are, therefore, interested in how the miniature locates a realm of play set apart from practical life, such that humans are free to ‘master' any relation, being, space or reality, immune to any apprehension or consequence regarding their actions; we would further suggest that this is especially true when such play is circumscribed by human-object relations. Through this material relation, the production and embodiment of a miniature copy amounts to a technology of control and self-idealization. This perspective broadly positions figurines in the project of world-making and also extends towards practices of magic and the protection of bodies and spaces, which may also provide potential themes for further study.

Hybridity and Animality

Claude Levi-Strauss once defined religion as the ‘anthropomorphism of nature' and indeed many societies choose to animate and anthropomorphize animals, plants, objects, and landscapes. Particularistic essences and characteristics from the natural world were deemed salient and efficacious in the human sphere. Hybrids crossing human, animal, and botanical species lead us to a consideration of boundaries and distinctions as experienced in these ancient civilizations. Our taxonomies must incorporate various recombinant identities based potentially upon human, animal and plant taxa. Tensions between categories that we find familiar have very different expressions in these other cultures, and raise the question of how this might reflect different forms of corporeal alterity.

The tensions and preoccupations are familiar to our own society and many others. The issue is change—the fundamental fact that one thing can become another. Hybridity, metamorphosis and change were important intellectual concerns. Ordinary people were fascinated by change as an ontological problem, not simply birth and decay as evinced in the life stages passing, but the porous structures of gender, ethnicity and kinship that constitute identity and alterity.

Hybrid representations assumed that those with cultural knowledge knew the story associated with the image and had referents for its spiraling associations. These images were metaphoric. Ontological metaphors allow us to comprehend a wide variety of experiences with non-human entities in terms of human motivations, characteristics and activities. From this point of view, the world is structured through metaphor, rather than metaphors simply operating as an embellishment or poetic device. Metaphors create new ways of conceiving of the world and they simultaneously destabilize and reveal it.

Our research, then, seeks to examine the nature of the boundaries between social and natural worlds, humans and others at Çatalhöyük. The enigmatic abbreviated human figurines have elicited prior identifications as diverse as ‘bird-men', miniature phalloi, and ‘humanoids' (Fig. 82b). Such ambiguity may suggest a potential blurring between categories of human and animal, in the case of ‘bird-men', or whole and part, in the case of anthropomorphized phalloi with human heads and ‘feet'. These forms press us to consider the importance of multiple viewpoints and material practices of exploring ancient conceptions of identity and difference.

Intentionality

Archaeologists have had serious difficulty in identifying intentionality in the archaeological record, especially in prehistoric contexts. But here, animal figurines might provide one arena for examining human agency within magical and ritual practices. Humans have multiple and complex relations with animals; in addition to the ontological concerns, humans relate to animals on a very pragmatic level. As sources of food, labour and even symbolic capital, animals often figure prominently into to routine social life. Wild animals in particular present a valuable and largely uncontrolled resource, which humans desire and endeavor to master and control. As such, these animals often become likely targets of human intentionality.

Animal figurines, which make up a substantial portion of the Çatalhöyük assemblage, constitute one material arena in which human intention may be visible. These figurines are particularly interesting as many bear clear indications of defacement and are deposited in interstitial spaces in walls and under floors. Notably this season, a cluster of six animal figurines (7958) was recovered in what appears to be a bin or bin partition within Space 100 of Building 49 in the 4040 Area. All of the objects were broken and fragmented, and a few of them bore ‘stab' or puncture marks.

Interestingly, Ali Turckan has noted the discovery of a similar deposit from a building (Building II, Level I) from a Late Neolithic settlement Köşkhöyük in Cappadocia (Özkan et al 2003). Several clay quadruped figurines have been recovered in a deposit under threshold of the storage area behind the main space of the building (Ibid: 200; figs. 5,6,7). The small number of finds inside the building suggests that the building may have been ‘cleared.” There is also evidence of fire.

Such examples of caching, intentional maiming, disabling, wounding and dissembling offer provocative windows onto the blurring of worlds, in some instances concrete and lived, and on other occasions imagined or desired. We do not view these material, symbolic acts as tantamount to acts against the actual beast, as such an argument is too reductive; rather, we consider such object-acts as bridges between abstraction and concretisation, bound by human intention. Here, the mimetic assertion of an altered material reality—the strong beast rendered lame and/or wounded—accomplishes a certain satisfaction and efficaciousness. It is also briefly worth mentioning here, that so-called ‘closure deposits' containing figurines also present an opportunity for examining human intention archaeologically (for possible example see context description for 10264.X1). Various contexts of intention, use and deposition underscore the idea that figurines represent radical forms of materiality that require thinking through in concert with the deep stratigraphies of social and cultural understandings .

Persons and Selves

Given that there are numerous vantage points when looking at human (and animal) forms, we must similarly allow for the possibility of various ways of interpreting those angles and perspectives. From our survey of the corpus, many small anthropomorphic figurines tend to be abbreviated in form (other terms that have been used include schematic- we avoid the use of the term humanoid altogether ); they are less than 5cm in height and generally have two stumpy protrusions at their base that probably serve as legs and are necessary for the object to stand upright. The trunk seems to be the focus for many so called anthropomorphic figurines; these small, casually made figurines were expediently shaped from silty clays. This notion of an abbreviated form may stand for a generic human, or a very simple shorthand for the human shape concentrating on the main bodily axis and lacking almost all extraneous detail. We hope to pursue questions around the nature of personhood as a visual category and how this may or may not converge with other material expressions of selfhood, as found in households, burials, wall paintings, and so on, across a range of experiential settings. Many of these anthropomorphic images are not explicitly sexed; they are simply highlighting the humanness of the form. This may connect to the plastered forms discovered by Mellaart: splayed human figures (albeit with arms are legs clearly demarcated) that were placed on wall surfaces. This reinforces a notion of personhood as non-discrete in terms of sexual markers.

Yet sexed figurines or body parts are also well represented in the corpus, as has been published previously. Underscoring the different viewpoints and angles that we argued above are part of the tactile nature of such objects, we similarly must allow for the possibility of sexual ambiguity or the blurring sexual features. One line of inquiry we wish to pursue is whether the Neolithic represented a sexual revolution, a period of ‘self' exploration practiced at an intensity not experienced before. For instance, does the assembling of people in clustered communities facilitate a way of seeing self differently, of exploring the contours of a sexed self in new ways?

While much has been made of the so-called ‘Mother Goddess' figurines and the predominance of female imagery on site, rather less attention has been paid to the equally evocative images of masculinity at Çatalhöyük. A priori notions of a female divinity weigh heavy on interpretive frameworks. This is an obvious shortcoming since a large corpus of parallel imagery in two and three-dimensional media has been published from sites such as Nevali Çori and Gobekli. At Çatalhöyük, as with most Neolithic sites, old scholarship always emphasised female representations and hence there needs to be a balancing up of male and female imagery through a consideration of masculinity and other forms of gendered experience. Maleness is strongly demarcated across a range of representations including wall paintings that feature mostly men and male animals with antlers and erect penises. The popularity of the hunting scenes at Çatalhöyük must also be taken into account. One could argue that the male of each species is generally more obvious and more highly elaborated, whether by horns, patterning or size and so on.

Although preliminary, from a visual analysis we found that in numerous anthropomorphic forms—largely the abbreviated types—the trunk of the body was not completely upright but bent forward, giving these examples a phallic resemblance. If one turns them around the trunk (with or without elaborated head) many resemble a penis (some have lines around the top that look like wrinkles) and the two stubby legs protruding forward contribute to the overall visual effect of male genitalia. This is only one possible interpretation and such a visual play may have been intentionally or unconsciously created.

The question of sexual ambiguity or synthesis should also now be considered key. The stone figurine found this season is a prime example (10264.X1, Fig. 4), since the head and neck suggest a phallic shape on a cylindrical base. Interestingly it shares visual similarities with Neolithic SE European masked figures as well as Cypriot figurines.

The Anatolian Neolithic

Appendix 1. Database structure

|

|

Appendix 2. FileMaker Pro Example Record:

Page 1

Page 2